With summer in full swing and the temperatures across the Far North soaring, there is no better time to head out to the Great Barrier Reef. With the sun shining, many tourists and locals are taking advantage of this string of good weather to head out to the reef and enjoy a snorkel and a dive. Tourism staff out at the reef are all too happy to greet these eager visitors and show them a great time. But those of us working out on the reef are also aware of a potential threat to the reef, a threat which can shake the very foundation of the reef ecosystem. And the worst part? We are completely powerless to stop it. We are talking about coral bleaching. To put it very bluntly, the Great Barrier Reef will most likely experience its third major coral bleaching event in two decades beginning in early 2016.

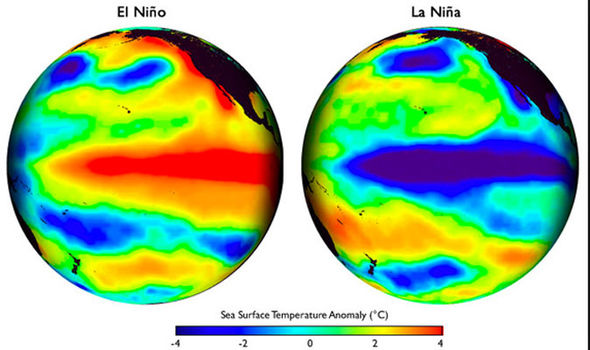

Coral polyps are actually translucent animals. Reefs get their wild hues from the billions of colourful zooxanthellae (ZOH-oh-ZAN-thell-ee) algae they host. When stressed by such things as temperature change or pollution, corals will evict their boarders, causing coral bleaching that can kill the colony if the stress is not mitigated. Currently, the global climate in in a state known as El Niño, and this puts the coral at higher risk of bleaching. El Niño is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central Pacific Ocean, and typically brings higher-than average water temperatures to the Great Barrier Reef. The risk of a major bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef would likely present when temperatures peak in March to April; the risk of severe bleaching would be more so in the event of a heatwave and less likely if cooling monsoons or a cyclone swept the north Queensland coast.

While traditionally thought to be caused mainly by high temperatures, new research suggests that other factors, including invasion by viruses, can also play a role in coral bleaching. In one study, a “herpes-like” virus was found infecting coral on the Great Barrier Reef, especially during the coral bleaching phenomenon. The study, undertaken by American and Australian researchers including James Cook University’s Dr Tracy Ainsworth, found a virus similar to herpes was one of several strains that could infect coral after it had been bleached. Further research is being done to determine the long-term impacts of these viruses on coral.

It is with all this new research in mind that scientists and reef staff are keeping a keen eye on the weather, water quality and coral characteristics. It will be for time to tell if the Great Barrier Reef experiences another bleaching event, or if we can dodge a bullet.